Ever the idealist, Lê Xuân Nhuận refused to participate in Nguyễn Cao Kỳ’s plot to seize power from his running mate Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. Instead, he informed the CIA, which took steps to assure that Thiệu would become the first president of the Second Republic of South Vietnam.

But Thiệu could not assert his power until he had dismantled the security apparatus Kỳ, as prime minister, had developed since 1965. And given that Kỳ’s apparatus was effectively providing security for Sài G̣n during the 1968 Tet uprising, Thiệu’s dismantling process took several months.

Be Sure to Visit the Series Homepage Daily for New Content!

The critical moment occurred in early May 1968, during the second Tet Offensive, when a sniper shot and seriously wounded Kỳ’s security chief, General Loan, outside MSS headquarters. Loan’s CIA advisor, Tullius Acampora, believed that forces loyal to Thiệu, backed by Americans, were responsible.

“Not only Tully, but many others believed that General Loan was shot by friendly fire,” Major Nguyễn Mâu recalled. “At that time, all efforts were concentrated to damage Kỳ’s equilibrium. The commander of Tân Sơn Nhứt Airbase, Colonel Lưu Kim Cuong, who was very faithful to Kỳ, was also assassinated by an unknown sniper.”

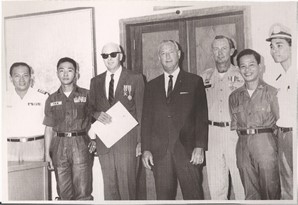

Senior CIA officer Evan Parker, director of the Phoenix Program (1967-1969) and senior CIA officer John Mason, his replacement, with US and Vietnamese Phung Hoang officers.

The dismantling process culminated in early June 1968 when a rocket fired from a US Marine helicopter gunship slammed into a wall within a schoolyard in Sài G̣n. Seven high ranking Kỳ officials, all of who had been invited to that location by their American advisers, were killed, including General Loan’s brother-in-law, two precinct police chiefs (one of who was Loan’s personal aide), and the Sài G̣n mayor’s chief of staff, who was Loan’s brother-in-law.

Also killed was Nhuận’s erstwhile boss from Ban-Mê-Thuột, Nguyễn Văn Luận, then a colonel serving as director of Police and Security in Sài G̣n. As recounted in Part 1, Luận in 1960 had given Nhuận, who had been banished from Hue, a chance to prove himself as chief of the unit’s criminal investigations team.

Four days after Kỳ’s men were assassinated in Sài G̣n, Thiệu appointed Colonel Trần Văn Hai as Director General of the National Police. Hai immediately dismissed Kỳ’s remaining precinct police chiefs in Sài G̣n and named Major Mâu (cited above) as chief of the Special Branch, a position outside the regular police command reporting directly to the prime minister. Around 150 special policemen were reportedly fired or arrested during this period of transition.1

Thiệu named his personal secretary General Nguyễn Khắc B́nh as CIO Director, and gradually replaced Kỳ’s cronies in the military and civil bureaucracy. In the process, Thiệu loyalists seized control of the gold and drug smuggling rings that were key to financing agent networks and ensuring the loyalty of warlords primarily interested in power and the four savors (tứ đỗ tường); women, opium, gambling, and alcohol.

During this period of transition, the CIA launched its infamous Phoenix program to “neutralize”, by any means, the leaders of the Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI). When the CIA created Phoenix in June of 1967, Kỳ and Loan vehemently opposed it as infringing on South Vietnam’s national sovereignty. But the CIA implemented the program over their objections, and Thiệu, having seen the results, soon authorized the creation of Phụng Hoàng, the Vietnamese version.

Several well-informed people, including Colonel Acampora, believed the CIA used its Phoenix forces to weaken Kỳ, and that the sniping of Loan and the assassinations of Colonel Cuong and the seven high-ranking Kỳ officials in June of 1968, were Phoenix operations.

There is no dispute that with the advent of Phoenix, the already vicious counter-insurgency achieved even greater levels of violence.

Nhuận in the fall of 1967 was chief of the Special Branch in II Corps, based in Pleiku. To assuage the CIA, II Corps Commander Major General Vĩnh Lộc agreed to discuss the implementation of Phoenix/Phụng Hoàng with a CIA delegation headed by the CIA’s Region Officer in Charge, Dean Almy. Lộc designated his chief of staff, Colonel Lê Trung Tường, to represent him in the discussion, which Nhuận attended.

As Nhuận recalled, Tường strongly objected when Almy announced that the RVN military would be required to support what was essentially a Special Police operation.

Military officers like Tường felt the new task was an unnecessary drain on their resources. But the CIA always got what it wanted, and in February 1968, Thiệu replaced General Lộc with Lieutenant General Lữ Lan. Not surprisingly, Lan and his chief of staff, Colonel Tôn Thất Hùng, fully embraced Phụng Hoàng.

The Phụng Hoàng program was soon in full swing. Guided by their CIA advisors, Special Branch officers in every region, province and district furnished local Phụng Hoàng Committees with information and documents, so that military operations could be directed against targeted VC cadres. At the same time, Special Branch officers retained and did not send information and documents relating to the clues and leads they were going to exploit in their clandestine intelligence operations.

As Nhuận explained, “The Special Branch now had two contradictory jobs: to exterminate the VCI on the Phụng Hoàng side; and to protect, in order to exploit and recruit, the VCI on the intelligence side.”

Nhuận, however, fully supported Phoenix. “I was so interested in the Phụng Hoàng Plan,” he said, “that I volunteered to give lectures at the Region II Phụng Hoàng Training Center, even though I was not a member of the Phụng Hoàng Committee.”

Nhuận felt that Phụng Hoàng was needed to prepare the police to preside over counter-intelligence operations when the war ended. There would come a time when US military forces would leave and only the Special Branch would remain to act against the VCI, whose members, as part of any negotiated settlement, would come to hold elected positions within the government.

“With peace, officials would come from different social segments, including adverse elements,” Nhuận said. “And Phoenix/Phụng Hoàng really did carry out its intended purpose until 1969, when US military people took over the program, along with US advisors from US/AID’s Public Safety Division who worked with the uniformed National Police.”

Transferring responsibility from the Special Branch to the military was, in Nhuận’s opinion, the mistake that doomed Phụng Hoàng. “The military people and police chiefs who took over the program from the Special Branch professionals were not as reliable or as well versed in intelligence operations. They could be trained, but only in how to make reports, not in knowing and understanding the factual conditions in the districts and villages where the real things happened.”

Special Branch (Ngành Đặc-Biệt)

In 1969, CIA station chief Ted Shackley issued instructions that CIA officers assigned to Phoenix should withdrew from involvement in the program. The plan, Shackley told me, “was to free up CIA resources to improve the quality of the intelligence product, to penetrate the Vietcong and the North Vietnamese supporting them, and to concentrate more against the North and Cambodia.”

The war was far from over, but the US and North Vietnam had begun secret negotiations. As part of “Vietnamization” – the transfer of responsibility from the Americans to the Vietnamese – Shackley also started distancing the CIA from the Special Branch. Under Shackley, CIA officers continued to work closely with the CIO, but focused more on unilateral operations.

The withdrawal of CIA support foretold a crisis of morale within the Special Branch. Not only did the CIA fund the organization, it insulated Special Branch officers from ambitious Sài G̣n politicians, province chiefs and military commanders who wanted to use them for selfish reasons. Some Special Branch officers had made enemies and were now exposed, including Nhuận.

In 1969 Special Branch headquarters in Region II was relocated from Pleiku to Nha Trang City on the coast, where Nhuận became deputy chief under Lieutenant-Colonel Nguyễn Văn Long, a military officer with friends in Sài G̣n who wanted to assert military control over the Special Branch. Long was not an intelligence officer, however, and Nhuận remained the CIA’s principal contact. Nhuận worked with Dean Almy until 1970, and with Almy’s replacement Bill Anderson and his staff from 1970 until 1972.

“I helped my CIA advisors by putting good members under their direct command,” Nhuận said. “I had my advisor’s Vietnamese assistant come to my office every day to take news and information from me.”

In November 1970, Prime Minister Trần Thiện Khiêm fired Lieutenant-Colonel Nguyễn Mâu, who Thiệu considered a potenetial opponent in the up-coming elections, and appointed Brigadier General Huỳnh Thới Tây as chief of the Special Branch in Sài G̣n. Colonel Long had departed under a cloud and Nhuận was once again director of the Special Branch in Region II. His immediate boss was Colonel Cao Xuân Hồng, the National Police chief in Region II. Nhuận describes Hong as “a professional civilian police officer who often sent me to meet the military people because I had been in the army. I met the military almost every day at least at the II Corps situation room.”

Nhuận focused on the propagation and statistical analysis of the Police Plan, along with his voluntary participation in Phụng Hoàng, as outlined in his book Cảnh-Sát-Hóa. Primarily, he was an expert on all facets of agent handling: from recruiting, processing, and testing an agent, to creating an operational plan which was set in motion when the agent was trusted to join the VC as an “infiltration” agent. If the agent could recruit a VC element in place, the plan was classified as “penetration” operation.

The interrogation section, located at the Province Interrogation Center (PIC), was only supposed to produce information and leads. Information was to be disseminated by the Study and Plans Section; and leads were to be handled exclusively by Special Operations (Tiểu-Ban Công-Tác Đặc-Biệt) officers within the Secret Services Section (Ban Mật-Vụ), who were trained as case officers in infiltration (Xâm-Nhập) and penetration (Nội-Tuyến) operations.

But military officers and CIA contractor officers assigned as PIC advisors used the PICs as operational centers to recruit, train, and run agents in clandestine operations, often with poor results. Sometimes the PIC advisor would develop agents and run operation by himself.

“It was confusing and difficult to evaluate such imposed special operations,” Nhuận recalled.

The Special Branch suffered another blow when a major reorganization of the National Police in 1970 stopped Special Branch operations at the district level. The problem was lack of funds, but the Special Branch, in Nhuận’s expert opinion, should have been allowed to operate at the village and hamlet level, where the VCI organized their cells.

“The US helped the government create a more amiable, less abominable police force,” Nhuận acknowledged. But it was a castle made of sand. And with the withdrawal of US advisors and funds, and the militarization of the police, the American Dream was replaced by a harsh reality that the Republic of Vietnam was still a developing nation, devoid of democratic institutions, faced with an implacable foe.

1Richard Critchfield, The Long Charade (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1968), p. 387.